Immigration History

Three waves define the pattern of Italian emigration to the United States and Canada and each wave brought with it a distinct group of immigrants. Read below a short history about each wave and its impact on Calascio.

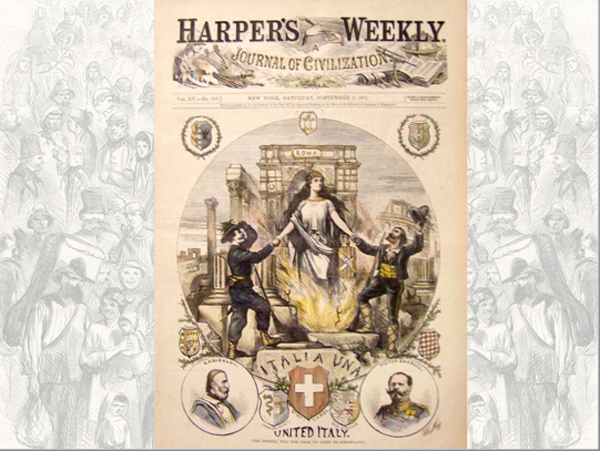

The First Wave (1830-1895) saw a predominance of skilled labor from Northern Italy heading primarily to urban centers in the Northeast. Italians in this period labored in the building trades of North America and performed skilled artisan work. Early arrivals entered the U.S. at Baltimore, Boston New Orleans and New York. By the 1880s, Italian immigrants numbered about 300,000 in the U.S. with another 600,000 arriving in the 1890s. During this period, South America (particularly Argentina) became another port of entry for Italians in addition to other nationalities.

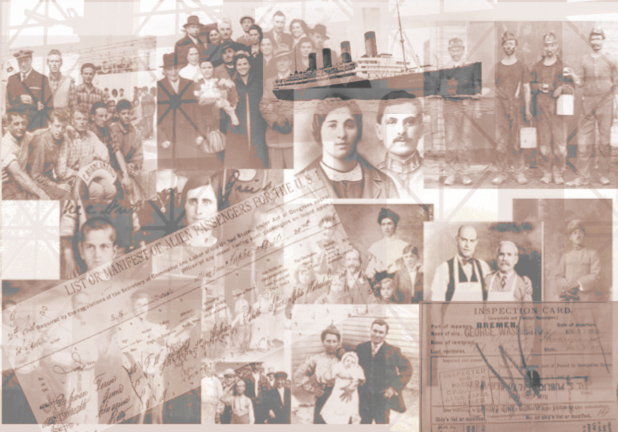

The Second Wave (1900-1914) coincided with the opening of a new immigration station on Ellis Island in New York. Nearly three million Italians arrived to the U.S. during this wave. The majority were peasants from the South who spoke regional dialects and were largely uneducated and unskilled. While a majority of the arrivals remained in the U.S. and Canada, about one third were itinerant, single men who returned to Italy and became known as ritornati. Italian women who were married often stayed behind while their husbands ventured across the Atlantic to earn money. Some husbands chose not to return to their families in Italy and instead, abandoned their wives overseas. On the other hand, a host of Italian women did emigrate during this period but some of them, after making the arduous trip, found life outside Italy not to their liking and returned to their village. In each case, these women faced a permanently unmarried status in Italy as vedove bianche –white widows.

A Third Wave took place in the period prior to and then immediately after the Second World War. This wave tended to include whole families as opposed to single workers. Most emigrants were fleeing political conditions before the war and subsequently they fled the devastation of their villages after the war. Portions of this wave were attracted to work in the booming automobile and steel industries of the U.S. and Canada.

Why Did They Emigrate?

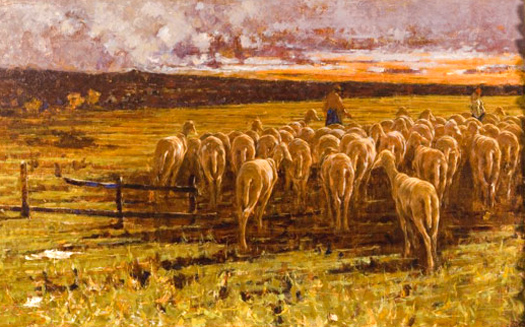

For hundreds of years the economy of Calascio was based on the trade of sheep for their wool. Families who owned sheep and/or the pastoral lands became very wealthy and hired village shepherds, farmers and laborers on a regular basis. By the mid-1800s, the wool industry in Italy began a slow decline and those who worked for the families needed to go elsewhere for employment. In addition, Southern Italy (Calascio included) went through a social change in the period following unification and this, along with other changes across Italy, had a negative affect on population growth.

According to an 1863 regional census the population of Calascio stood at 1,391 persons, not including several hundred residents in Rocca Calascio. Of the 1,391, there were 826 adults and 565 children under the age of 16. Two-thirds of the population was female reflecting an ongoing loss of men who either left the village during la transhumanza (wintering of sheep just south of Abruzzo) or who left Italy to find work elsewhere. Of the total population in 1863, there were 69 landowners and 81 shepherds in Calascio along with a number of bakers and laborers. Nearly all adult women and young girls (a total of 502) worked as filatrici -- spinners of wool. Counting all children and adults, only 483 males resided in the village permanently in 1863 comprising just 34% of the population.

What was the affect?

Due to continual emigration from Italy, Calascio lost an average of 45 citizens a year from 1888 (when travel data began) to 1900, when the annual loss figure exceeded 100 persons. From 1898 to 1901, a reported 469 people left Calascio and most never returned. Once the transhumanza was phased out, it cut-off the village's long-time employment opportunity for males. Emigration swiftly increased and the combined populations of Calascio and Rocca Calascio fell by 42% from 1901 to 1931 (1,938 to 1,119) according to Italian census data. In addition to plentiful work overseas, outside the village there were jobs in the towns of L’Aquila, Pescara and Rome. For example, in 1900 the nearby village of Ofena received hundreds of new residents as its grape and wine industries flourished.

By 1961, the population of Calascio declined to 616 and in 1991, it stood at 224. By 2017 the village's population fell to just 134 residents but that number reflects an aging population verses ongoing emigration.

The Earliest Arrivals to the U.S.

While Calascini were emigrating as early as 1880, it is likely the first villager to permanently settle in the U.S. was Vincenzo Novelli S.J. (1829-1892) a Jesuit missionary who arrived in New York in 1871. Brother Novelli went to Las Vegas, New Mexico and then to Pueblo, Colorado, where he worked among Native American tribes. His nephews followed him; Giacinto Fulgenzi (1857-1932) and his brother Antonio Fulgenzi (1855-1921) immigrated in 1885 and 1887 respectively. They remained in New Mexico until their deaths. Domenico Contasti (1870- ?) and his sister Luisa (1874 – 1899) joined the Fulgenzi brothers around the same period. Their ultimate whereabouts and descendants remain unknown.

Another early immigrant was Francesco Ciota (1850-1909) who settled in Riverton, Illinois in 1893. Ciota and his wife raised a large family in Illinois. Working first as a coal miner upon arrival, Ciota ultimately became mayor of Riverton.

Da pastore a minatore

During the late 1890s and early 1900s, coal mining in the U.S. attracted European immigrants seeking work in unskilled jobs. Italian males made a ten-day journey across the Atlantic Ocean to secure employment in the mines with the idea of saving their money to either get married (back in Italy) and then return to the U.S. to raise their family or, earn enough in the U.S. to return to Italy and live a comfortable life. In 1896, a U.S. commission on immigration estimated Italian immigrants sent and/or took home between $4 million and $30 million each year, and “the marked increase in the wealth of certain sections of Italy can be traced directly to the money earned in the United States.”

Compra un mulo o compra un biglietto

Life in Calascio up until the post-Second World War era was neither easy nor comfortable. Few homes had running water prior to 1911 which meant villagers (typically young women) set-foot each day in the early morning to fetch water located hours away. A majority of the ancient, stone homes were cold with only one hearth to a family keep warm. Electricity was scarce as late as the 1940s. The village streets were made of compressed dirt that changed to mud in the spring and winter. While food was appetizing it was limited in variety. Meat was scarce and the villagers' diet often lacked vital nutrients. Without proper medicine or medical attention in the village, epidemics were common throughout the history of Calascio and their outcome resulted in scores of deaths for the young and elderly.

In Calascio, married women worked in the home and raised children. If single, their work was limited to being a contadina, (field hand), a filatrice (spinner) or cardatrice (wool comber), to name a few occupations. If a man was not a member of the village’s landowning class he had little choice but to work for a landowner as a laborer, field hand, farmer or shepherd. Calascio had a semblance of a middle class in the form of the campagnoli. These were families who owned a parcel of farmland but lacked resources to hire field workers and so they directly took care of their own property.

If a prospective emigrant saved their money, and it took years to save it, they had a choice as to how to use it by either remaining in the village or putting the funds towards a life abroad. The choice for most working-aged males in Calascio was simple: compra un mulo o un biglietto per L'America (buy a mule or a ticket to America). Vincenzo Zara, a life-long Calascio resident, uttered this phrase when Calascio.com interviewed him. For example, in 1906 a steerage class ticket from Naples to New York cost on average $36.00, or about $1,080 today. Zara had ties to Riverton, Illinois because his father was born there in the early 1900s and, Zara’s maternal grandfather earned money by working in the mines of the U.S. He chose to return with his family to Calascio. Numbered among the ritornati of the village, Zara’s family is the exception to Calascio’s emigration pattern as the majority who made outbound transatlantic passages never returned.

The ebb of Italian emigration

In North America during the Second World War, Italian immigrants (along with Germans and Japanese) were considered enemy aliens. Ironically, the welcoming U.S. symbol of Ellis Island was changed over to a detention center for immigrants during the war. With the return to peacetime, the U.S. re-opened its doors to immigration and loosened quotas on various nationalities. In Europe, Belgium and France became new destinations for coal mining and so Calascini emigrated to those countries in addition to destinations in South Africa and Australia.

By the 1960s, travel by ocean liner was less common and emigrating Italians tended to arrive to destinations by airplane. While Calascio’s immigrants historically worked in coal mining, that industry declined in the 1960s and as a result, the third wave of immigrants were attracted to jobs in the garment industry, grocery business, the restaurant business and a host of other trades that fueled the post-war economies of the world.

Today, thousands of descendants of Calascini immigrants are living across the U.S. and Canada. Each subsequent generation owes their success to the ancestors who travailed before them.